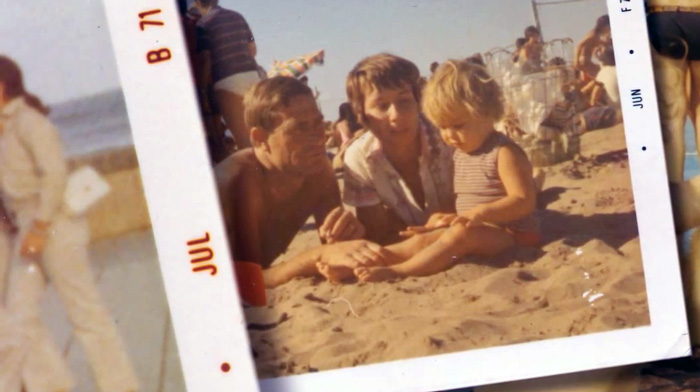

When I was 4 and a half years old my father died. Everything changed that day. I grew up repeating the same short answer whenever anyone asked me about him: “My father died in a train accident on September 13th, 1973”. An answer that provided no details, meant nothing to me, did not explain how or why, and yet eventually became deeply rooted in the blanket of silence our family life was wrapped in. The same silence that held me firmly in its grip as both my family and the society around me at that time neglected to speak about him and taught me to avoid asking questions. And I ended up forgetting my father.

Thirty years went by before I could replace suspicion with questions about the official account of the event. I was able, at last, to talk about it with my uncle Boris. My father had been found dead at the side of the railway track in the Avellaneda train station. There, near a strip of wasteland, an engine driver had found his already lifeless body. My mother’s family and some of her co-workers decided on our behalf – my mother’s, my brother’s and my own – that the “accident” story would be kinder than the facts.

¿What other issues were concealed at the same time the false account of my father’s death was concocted? ¿What inconspicuous acts of complicity, either prompted by grief over loss in some cases or due to differences in social class and political ideas in others, concealed the more controversial aspects of the man who had been my father?

The truth about his death gave me, at last, the opportunity to set off on this personal journey to reconstruct his full identity as a human being: a father, a construction worker, a political activist, and also, previous to that, a poor kid from the wide, lonely ranges where he had once lived. But most of all it helped me find a way to understand the true reasons underlying the false story made up a a result of the ideological and political views of the people that put it together in the distant 70’s, when class interests disputed every inch of the world. This is the story I want to tell: a personal story. I intend to describe the texture of the fabric woven by daily contact, by complicity and concealment on the part of family members and close relations, in a historical period crisscrossed by diverging conceptions of the world; to examine the actions that, though well-meaning, erased identities, concealed historical processes and brought about damages that continue to have an impact today. Maybe, to a certain extent, I want to tell the story I myself would like to see in a film depicting that period. I feel it is from this standpoint that I can contribute to a more complete understanding of the events, using images and words to tell what cannot be fully told yet.

To tell this story I need the tools a film provides. This is the language I have chosen to voice my experience, unique inasmuch as it is personal, but also common to many other Argentinians in my generation.

In this film, which I approach from the deepest corners of my self, I will describe gestures, time lapses,silence, oblivion and the relentless search to recover an image, even from dreams or makebelieve or by rearranging imaginary scenes, out of longing for what can no longer be lived or what could never be treasured as a memory. A documentary, inasmuch as it brings to light “truth”, is for me the most genuine means of expressing the inbound quality of this journey that has helped me put together the father circumstances had robbed me of , first through death, later as a result of a lie and, finally, by casting a shadow on his past existance.

Some experiences cannot be put into words as, for instance, an image I have no recollection of, in which the father carries his daughter on his shoulders and walks very slowly along the beach, looking at the sea. This is the reason why I need images, why I want to make this film.

Some experiences cannot be put into words as, for instance, an image I have no recollection of, in which the father carries his daughter on his shoulders and walks very slowly along the beach, looking at the sea. This is the reason why I need images, why I want to make this film.

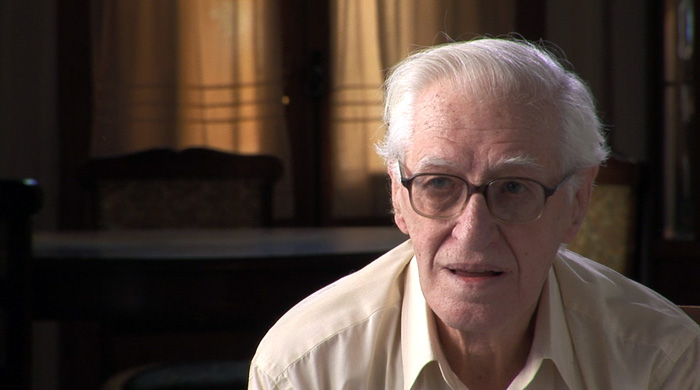

Mariana Arruti

Director